Parents – talk to your kids about mental health. Even if it’s awkward

Source – Hannah Jane Parkinson The Guardian Online.

When I was younger, I’d have to make an excuse to leave the room whenever sex scenes came on the television. I learned to sniff out at a bedroom scene within 30 seconds and escape to make tea, or feign a yawn and head off to bed.

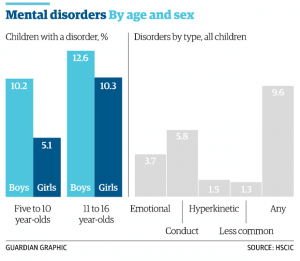

There are many things it’s difficult to talk about with parents. Mental health, apparently, is one of them. Given that one in 10 young people experience mental health issues, it is worrying that 55% of parents in the UK have not discussed mental health at all with their children, according to a new study from the Department of Health and Time to Change. Even more shocking is that 45% of parents interviewed said they haven’t had this conversation because mental health “is not an issue”.

More than 850,000 children aged between 5 and 16 in the UK have a mental illness. Child and adolescent mental health services are struggling with soaring referrals and admissions. It is thought that half of diagnosable conditions manifest before the age of 14 and 75% by 21. A study in October found 62% of teens had searched for information about depression on the internet.

It is difficult enough to experience a mental health condition or episode at any age, but these issues can have a particularly serious impact on teenagers’ future. A-levels don’t wait for you to pull out of depression. Months of education can be missed as you battle an eating disorder or recover from an episode of psychosis.

https://youtu.be/TBlt-UQVSLQ

When the stigma that surrounds mental illness is still so prevalent in society, it’s no wonder so many parents feel uncomfortable discussing the topic. They might have had their own struggles, adding to their unease. But mental health shouldn’t be a taboo subject, and the sooner children learn this the better.

It is much better to raise the topic of mental health before an episode occurs, since talking or accepting help can be especially hard when you’re in the grip of illness. You can feel ashamed, or burdensome, or worthless.

I remember, as a 16-year-old, in a duvet, wanting to die. Not really understanding why I wanted to die, and certainly not wanting to talk about why I wanted to die. Friends passed their exams and went to nightclubs; I shuffled through New Order songs trying to pick an appropriate funeral track. So far, so teenage.

And that’s the thing – if your child is choosing New Order songs for their impending funeral, or is suddenly reading Sylvia Plath’s diaries, it might be nothing. But it absolutely might be something; it might be a kid searching to find context for this thing they’re feeling, because they don’t recognise it and it scares them.

Sure, it’s not unusual for kids to start ratcheting up the kohl and railing against the world, but depression and other mental health conditions present themselves in many different ways – some fit a stereotype, most absolutely don’t. Not all are about feeling low. It’s important not to stigmatise teens as attention seekers, or melodramatic, in case there’s an underlying issue.

I can’t imagine how heartbreaking it must have been for my own mother to sit down and write a letter to me when I was a despondent recluse, pushing it under the door at a time when I refused to communicate. For months I would rise long after she had gone to bed, climbing back under the covers as the sky turned from navy to grey.

Nobody is suggesting it is easy. Every parent must know the desperate feeling of not being able to help their child in pain. So anything you can do to educate a child about issues that may occur, increasing their chance of communicating if they do have trouble, is positive.

This is more important than ever, as studies have found that social media pressures, cyber and offline bullying and body image concerns are affecting teenagers in ways that we’re only just learning about.

Of course, the onus is not just on parents to help children and adolescents with mental health problems. The government must do more to improve funding for services. Initiatives such as the new mental health passport for young people and the cross-party campaign for parity of esteem with physical health are positive steps, and George Osborne has just earmarked another £600m for mental health. But this must be set against the £50m worth of cuts to child and adolescent mental health services over the course of the last parliament (£600m for all mental health services in total). We need to do more.

Every single school needs to have access to a dedicated mental health professional. The government has said it hopes to achieve this (while stating that 86% of secondary schools already have access to a therapist; let us know in the comments if this is something you recognise). The media, too, can play its part.

But parents – please talk to your kids about mental health, just as you would about sexuality, or race, or gender or physical health. Talk to them about your mental health; about their mental health. Talking might be awkward, but the alternative? It doesn’t bear thinking about.

• The Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 in the UK. If you live outside the UK, a list of organisations providing support internationally can be found here.